Good instructional design is simply not enough to magically see a design project from its inception to its completion. Instructional designers require project management skills. Makes reasonable sense, given that instructional designs are projects, too. The project, not just the design, needs direction and management. But let’s dig a little deeper.

It’s time to consider the delicate dance between these two professions and skill sets. It’s time to see what it looks like when project management drives an instructional design project. Let’s focus on the critical piece of task analysis.

I’m currently working on the project plan for the second instructional unit of the curriculum I’m creating – Timeless Tales with Paige Turner – an online reading intervention for struggling secondary students.

It’s important to note that I didn’t say “instructional design plan”. I said “project plan”. While the two work very closely in tandem, they aren’t the same thing.

Here’s how it works:

Instructional Design Plan

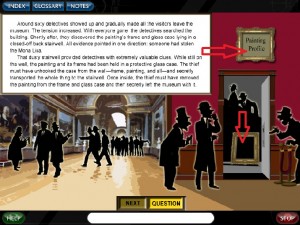

The reading comprehension skill targeted in the first lesson of the unit is identifying plot elements. When I designed this lesson, I followed a loose version of the ADDIE process.

Analysis

First, I analyzed the state assessments students have to take to determine whether questions about identifying plot elements were featured prominently. They were.

Next, I analyzed student performance on these questions to determine whether students demonstrated a need for additional support or intervention with this skill. They did.

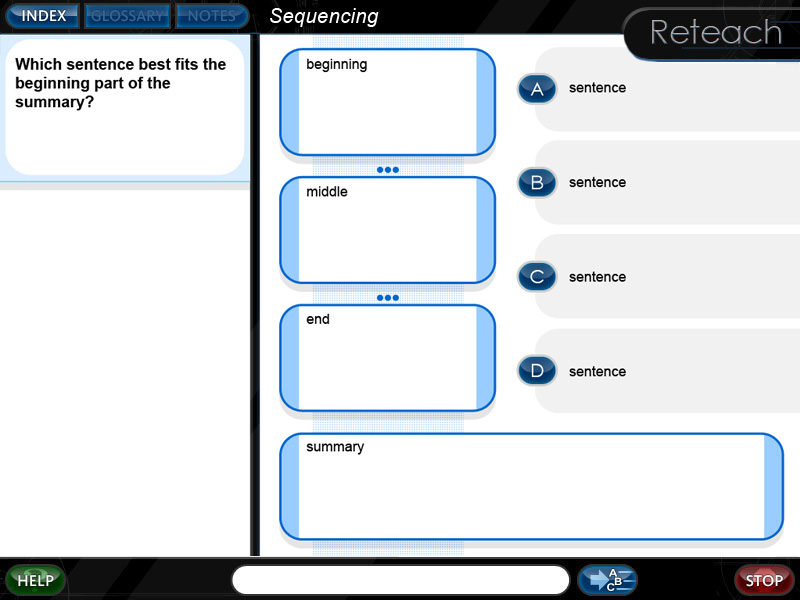

Then I ranked the skill along a continuum to determine its placement within the overall program. I used Bloom’s Taxonomy and the logical progression of reading skills in my ranking system, until I determined that first, students needed to understand how to sequence events in a story. Only AFTER understanding how to sequence a story’s events could students break those events down into identifiable plot points.

Then I ranked the skill along a continuum to determine its placement within the overall program. I used Bloom’s Taxonomy and the logical progression of reading skills in my ranking system, until I determined that first, students needed to understand how to sequence events in a story. Only AFTER understanding how to sequence a story’s events could students break those events down into identifiable plot points.

So, according to the instructional design plan, the skill of sequencing was taught in Lesson 1.1A, and the skill of identifying plot elements is to be taught in Lesson 2.1A.

Design

In order to determine exactly what to teach and how, I designed the primary learning objective for the lesson. The task statement comes directly from the state and Common Core standards for middle school readers. I created the conditions and standards to align with expectations on state exams and also to work within the technological boundaries of our program. The conditions and standards generally form what is known as a performance measure.

The whole objective statement, when read together, presents a clear picture of exactly what students are expected to be able do at the conclusion of the lesson, under what conditions, and with what degree of accuracy to demonstrate mastery.

- Students will be able to identify the five major plot elements in a short work of fiction with 80% accuracy as demonstrated through their responses to multiple choice questions presented in an online format.

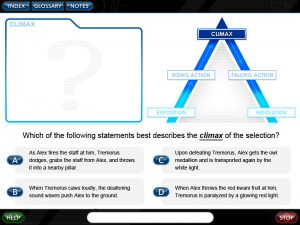

This overall learning objective can further be divided into pieces. What exactly are these plot elements which students are expected to identify?

This breakdown creates five objectives, five learning tasks. Many instructional designers or project managers would refer to these as main tasks. I’ll spare you the repetitive read. Just note that I created a separate objective/task statement for each plot element.

- Students will be able to identify the EXPOSITION/RISING ACTION/CLIMAX/FALLING ACTION/RESOLUTION in a short work of fiction with 80% accuracy as demonstrated through their responses to multiple choice questions presented in an online format.

There are also some secondary tasks, or prerequisite tasks, if you will. Many instructional designers and project managers would refer to these as supporting tasks. Allow me to demonstrate (again, sparing repetition):

- Students will be able to correctly define the academic term(s) EXPOSITION/RISING ACTION/CLIMAX/FALLING ACTION/RESOLUTION with 80% accuracy as demonstrated through their responses to multiple format questions presented in an online format.

- Students will be able to correctly identify examples of EXPOSITION/RISING ACTION/CLIMAX/FALLING ACTION/RESOLUTION with 80% accuracy as demonstrated through their responses to multiple format questions presented in an online format.

If I were to order these learning tasks appropriately for students, they would FIRST need to be able to define the terms, then recognize isolated examples of them, and finally, they would be able to identify the elements of plot within a fiction text.

Project Plan

Now, when we get to the tail end of the design phase of ADDIE, and into the development and implementation phases, project management comes into play. Now, the learning tasks above (for students) are correlated to project tasks, like this:

- Students will be able to identify the five major plot elements in a short work of fiction with 80% accuracy as demonstrated through their responses to multiple choice questions presented in an online format.

If this is the primary LEARNING objective, the project task is to create and deliver the lesson and the multiple choice assessment mentioned in the learning objective. In this case, that primary project task absolutely needs to be divided into smaller, more manageable tasks to help keep the development of the project on track. Those might look something like this:

1. Create and deliver Lesson 2.1A – Independent Practice to production.

1.1. Deliver fiction passage to art for illustration.

1.1.1. Draft fiction passage with clear plot points.

1.1.2. Submit fiction passage to content editing.

1.1.3. Submit fiction passage to copyediting.

1.1.4. Revise and finalize fiction passage.

1.2. Finalize Plot Elements Graphic Organizer.

1.2.1. Create Plot Elements Graphic Organizer concept.

1.2.2. Submit to user interface department for rendering.

1.2.3. Obtain final Plot Elements Graphic Organizer from UI department.

1.2.4. Draft instructional dialogue and multiple choice questions surrounding plot points found within the passage.

1.3. Deliver instructional dialogue for scripting.

1.3.1. Submit instructional dialogue and multiple choice questions to content editing.

1.3.2. Submit instructional dialogue and multiple choice questions to copyediting.

1.3.3. Revise and finalize instructional dialogue and multiple choice questions.

1.4. Deliver script to production team.

1.4.1. Create lesson script using fiction passage, graphic organizer, instructional dialogue, and multiple choice questions.

1.4.2. Submit lesson script to multimedia team for functionality review.

1.4.3. Submit lesson script to copyediting.

1.4.4. Revise and finalize lesson script.

1.5. Deliver reporting matrix to engineers.

1.5.1. Update skills matrix document for the lesson to reflect the number of multiple choice questions and number of correct responses required for 80% mastery.

1.5.2. Post skills matrix document for engineers.

In this way, the instructional design outlines what students are expected to do, while the project plan outlines what the instructional designer has to do in order to complete the lesson.

There are some good resources out there for task analysis, which can support instructional designers in determining and outlining their project tasks.

There are a few things to note here.

First of all, the learning tasks should be sequenced according to the order in which students need to be able to do the tasks. This makes for a logical, sequential lesson. It also ensures that students master the basic pieces or steps before being expected to master the overall learning objective.

The same goes for project tasks. They should be sequenced according to the order in which they should be accomplished. The five main tasks above should be completed in the order listed. The secondary, or sub-tasks beneath each should also be completed in order.

Another thing to note is that in a systematic instructional design, many project tasks will be repeated, with slightly different content.

Task #1 is to deliver the independent practice segment, because I’ve chosen to begin with the assessment and then build the lesson around it.

Task #2 for this lesson will probably be to deliver the introduction/teaching segment, in which the terms will be defined, and isolated examples presented. Most of the sub-tasks here will be unique to that segment.

However, when we get to Task #3, the guided practice segment, which uses another passage and more multiple choice questions, most of the sub-tasks from Task #1 will be repeated.

I bring this up not to belabor the point or exhaust the poor reader with repeated mentions of the word “task,” but to demonstrate this simple notion:

When the process for completing an instructional design project is well-defined, every task is not unique.

The tasks repeat themselves BECAUSE the process is solid. (Draft, edit, revise, finalize.) This is no different from any other logical process. The instructional designer or instructional design team can see the goal ahead and then follow protocol, or a series of repeating steps, to accomplish that goal.

The tasks repeat themselves BECAUSE the process is solid. (Draft, edit, revise, finalize.) This is no different from any other logical process. The instructional designer or instructional design team can see the goal ahead and then follow protocol, or a series of repeating steps, to accomplish that goal.

Systematic doesn’t always mean boring. Sometimes, it means efficient.

And that’s how you can use instructional design and project management concepts in tandem to keep a project on track, within the proverbial scope and budget and timeline. But that’s a discussion for another day…

References

Austin, I. (2011). Instructional Design Basics – ADDIE Analysis. Retrieved from digitizedi.com: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_l7Y2jVGoIc&list=UUcIEy4X4RvXJu92QIuGto7A&index=6&feature=plcp

Chapman, A. (2008-2010). Bloom’s Taxonomy – Learning Domains. Retrieved from Business Balls: http://www.businessballs.com/bloomstaxonomyoflearningdomains.htm

Churches, A. (2009). Bloom’s Digital Taxonomy: It’s not about the tools. It’s about using the tools to facilitate learning. http://edorigami.wikispaces.com.

Clark, D. (2011, September 26). ADDIE. Retrieved from Big Dog and Little Dog’s Performance Juxtaposition: http://www.nwlink.com/~donclark/history_isd/addie.html

Common Core State Standards Initiative. (2013). English Language Arts Standards: Grade 6.

Cox, D. M. (2009). Project Management Skills for Instructional Designers. Bloomington, IN: iUniverse.

Culatta, R. (2011). Instructional Design. Retrieved August 30, 2012, from ADDIE Model: http://www.instructionaldesign.org/models/addie.html

Hodell, C. (2011). ISD From the Ground Up: A No-Nonsense Approach to Instructional Design. Chelsea, MI: Sheridan Books, Inc.

Istation. (2012, June). Istation Reading. Retrieved September 3, 2012, from Istation: http://www.istation.com/Curriculum/ReadingProgram

Rooij, S. W. (2010, November 5). Instructional design and project management: complimentary or divergent? Association for Educational Communications and Technology.

Texas Education Agency. (2009). Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills: English Language Arts and Reading (Figure 19). Austin, TX.