“One must always be prepared for endless and riotous waves of transformation” ~E. Gilbert

Imagine you are dressing for a party. You have been planning your attire for weeks. You have purchased the perfect dress (bear with me, fellas), shoes, and jewelry to match. You try on the dress, examine yourself in front of the mirror, and – no! – you notice a snag in the dress. Right across the front, there it is. A most obvious, gnarly snag in your otherwise perfect party dress.

Well, clearly this won’t do. You quickly evaluate your options. You could skip the party all together. You do have a few other dresses that could work. After analyzing and weighing all choices, you settle on an old favorite from the back of the closet, give yourself one last glance in the mirror, and head out to the soiree, feeling a touch disappointed but relatively put together.

Well, clearly this won’t do. You quickly evaluate your options. You could skip the party all together. You do have a few other dresses that could work. After analyzing and weighing all choices, you settle on an old favorite from the back of the closet, give yourself one last glance in the mirror, and head out to the soiree, feeling a touch disappointed but relatively put together.

Now, what if we expand this metaphor a bit? Imagine you aren’t dressing for a party, but for a huge theater production, as part of the costumed chorus line? What if the costumes had been designed, selected, fitted, and purchased by a whole crew of stakeholders for the production? What if these stakeholders had decided upon and bought into every single detail of your intricate costume? And what if suddenly, while dressing for the production, you examined yourself in front of the mirror and – no! – discovered a snag in the costume. Right across the front. A most obvious, gnarly snag in your otherwise perfect costume.

Well, clearly THIS won’t do, either. But here’s the catch. You’re not a lone wolf anymore. It’s not going to work to just change your costume. You really can’t even decide on or implement a repair strategy or any other solution without the knowledge, input, and buy-in of the stakeholders involved in the production. You can’t just grab the first replacement you see and go out there on stage, the only blue dancer in a sea of pink ones. This is simply not a change that can be made in a vacuum.

Imagine the first scenario as a single person performing a single task. Sometimes, change can be made on the fly with little consequence.

Imagine the second scenario as an instructional design/project team performing a series of tasks with a collective goal.

Apply Change Management Concepts to Instructional Design Project Management

Like everything else in the world of instructional design project management, change requires careful analysis, clear processes, and communication.

While executing even the most well-designed project, there are few important things to consider:

1. Milestones – Evaluation and analysis of a project’s success need to take place at more than just the finish line. Building clear milestones into the project execution plan enables ongoing project monitoring. These milestones can be based on completion alone, but ideally, they’re also based on quality. Ideally, each milestone has an estimated completion date, a party or team responsible (for accountability), and at least some form of a quality or completion measure so that team members and stakeholders can assess whether the milestone has indeed been accomplished towards the successful completion of the project.

In keeping with our metaphor/example here, stepping in front of the mirror before the big production did not signal the completion of the production. If that production were a project being managed, that moment wouldn’t have been the finalization or delivery of the project. It would have been a milestone. The good news is that you stopped to look in the mirror at all.

2. Quality Controls – Throughout the execution of the project, quality controls need to be applied. These may be applied to the milestones, as described above, or they may be applied to the project processes themselves.

In this case, perhaps a few quality controls weren’t executed, or a few milestone quality controls missed. Was the costume engineer supposed to give all costumes a final check before the production to ensure no rips or snags?

3. Change Management Processes – As you’re hitting milestones with project execution, and you’re applying quality controls to measure the success of those milestones, you’ll need to have clear processes in place for managing change. Chances are about 99.9% that at least one milestone or quality control will indicate the need for change. Change on a project requires analysis and evaluation. Stakeholders have to agree that the proposed change is beneficial to the project outcomes. And communication is critical.

In our costume example, there might already be a process in place to satisfy the question, “What should I do if my costume is damaged?” Then again, there might not. Either way, the need for a change must be communicated. Stakeholders must analyze and weigh the options, and then, a change must be made and documented. Perhaps the costume procurer was wise enough to order backups. Perhaps there is a talented tailor on site. One can hope, right?

Change Is Inevitable

No matter how well designed a project plan is, the inevitability of change upon execution exists. If the instructional design/project manager does not have a plan for managing change, the project will suffer. The timeline might suffer as change requests are accommodated. The product itself might suffer if the change requests are not properly or fully evaluated in terms of the big picture goals of the project. So the ISD/PM has to have a plan for managing change. It’s just as essential as having a good starting design.

Change management as a part of project execution can be a tricky thing. The instructional design project manager has to ensure that processes are in fact in place, but at the same time, those processes have to be carefully designed so as to neither arbitrarily encourage nor discourage change.

Change needs to happen when the project will benefit. But change cannot be  such a free-flowing event in a project’s execution that it unnecessarily throws the whole project off track or extends the scope, schedule, or budget beyond stakeholder approval.

such a free-flowing event in a project’s execution that it unnecessarily throws the whole project off track or extends the scope, schedule, or budget beyond stakeholder approval.

Change Management

Though these may vary widely depending on the complexity of the project and/or the change management process itself, the basic components of change management are:

- Identify a need/rationale for change (often through quality management processes)

- Request the change (communicate to project team and/or stakeholders)

- Analyze and evaluate the change (risk of change, risk of not implementing change, impact on scope, schedule, budget)

- Approve or deny the change (communicate to project team and/or stakeholders)

Change-related documents may include a change request form, a change log, a change analysis/risk analysis form, and/or a change report. There are several tools available for developing strong change management processes.

Here are just a few:

Project Management Foundations – Managing Change

Simple Steps to Manage Your Project Changes

Bottom Line

The bottom line is that without a solid change management process in place, your project is likely headed for stormy weather. Either no changes will ever be made, and the project is likely to contain gaps, flaws, or mistakes, or change will creep up on your project and soon turn out of control, extending the scope, the schedule, and almost always the budget for your project.

In short, get a process in place. Know what to do when the costume fails three minutes before showtime. Because chances are good that no matter how awesome your project plan is, something will need to be changed.

References

Cox, D. M. (2009). Project Management Skills for Instructional Designers. Bloomington, IN: iUniverse.

Rooij, S. W. (2010). Project Management in Instructional Design: ADDIE is not enough. British Journal of Educational Technology, 41(5).

They have to understand the stakeholders, the goals of the project, and the limits within which the project must be completed. They have to understand and be able to articulate the

They have to understand the stakeholders, the goals of the project, and the limits within which the project must be completed. They have to understand and be able to articulate the  An instructional design project manager has to be able to swing like a pendulum between the very broad, high-level aspects of a project (overall goals and scope, timeline, and resources) all the way down to the minutia. And all of the facets of a project must be documented and communicated.

An instructional design project manager has to be able to swing like a pendulum between the very broad, high-level aspects of a project (overall goals and scope, timeline, and resources) all the way down to the minutia. And all of the facets of a project must be documented and communicated. We have the high-level program outline and scope and sequence for the curriculum, which list the overall unit themes and the primary targeted skills.

We have the high-level program outline and scope and sequence for the curriculum, which list the overall unit themes and the primary targeted skills.

The tasks repeat themselves BECAUSE the process is solid. (Draft, edit, revise, finalize.) This is no different from any other logical process. The instructional designer or instructional design team can see the goal ahead and then follow protocol, or a series of repeating steps, to accomplish that goal.

The tasks repeat themselves BECAUSE the process is solid. (Draft, edit, revise, finalize.) This is no different from any other logical process. The instructional designer or instructional design team can see the goal ahead and then follow protocol, or a series of repeating steps, to accomplish that goal.

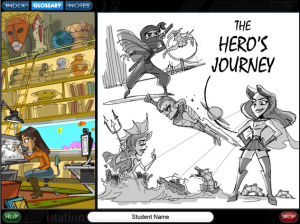

During my first year at Post, most of my work at Istation was theoretical, in that I was mapping out the path students would take through the program. I studied the state assessments to pinpoint the skills they’d need in order to graduate. Then, I planted these skills in the context of the overreaching theme of the hero’s journey and the power of storytelling to shape and impact human history.

During my first year at Post, most of my work at Istation was theoretical, in that I was mapping out the path students would take through the program. I studied the state assessments to pinpoint the skills they’d need in order to graduate. Then, I planted these skills in the context of the overreaching theme of the hero’s journey and the power of storytelling to shape and impact human history.

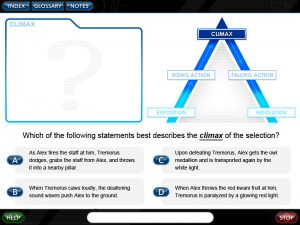

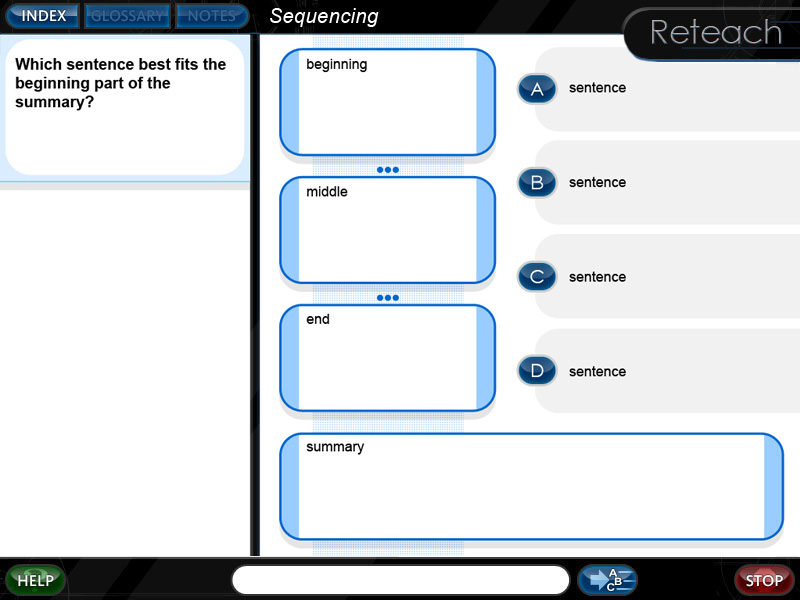

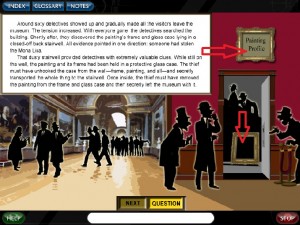

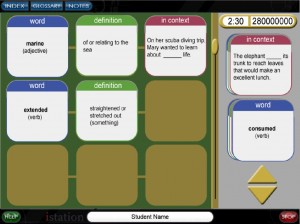

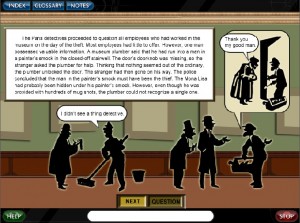

Most notably, and also most recently, we’ve also created templates for each activity, so that every lesson begins with metacognitive strategy instruction and an explanation of terms. Then we introduce a guided practice activity surrounding a story or nonfiction text. We finish each lesson with an independent practice activity that mirrors what students will experience on their state reading assessments each spring and also aligns with our own separate benchmark assessment.

Most notably, and also most recently, we’ve also created templates for each activity, so that every lesson begins with metacognitive strategy instruction and an explanation of terms. Then we introduce a guided practice activity surrounding a story or nonfiction text. We finish each lesson with an independent practice activity that mirrors what students will experience on their state reading assessments each spring and also aligns with our own separate benchmark assessment. Lesson 4.1A – Author’s Purpose

Lesson 4.1A – Author’s Purpose View and Perspective

View and Perspective

If the ultimate goal of any instructional designer is to create a course that imparts knowledge and changes behavior, then the

If the ultimate goal of any instructional designer is to create a course that imparts knowledge and changes behavior, then the  See, when you get past all the thinking that goes into the analysis and design phases of ADDIE, in the development phase, it’s time to actually create the course. It’s sort of like the midterm exam for the instructional designer, because this is the part in the process where the designer gets to test whether he or she conducted adequate analysis up front and/or whether he or she thought of EVERYTHING in the design plan.

See, when you get past all the thinking that goes into the analysis and design phases of ADDIE, in the development phase, it’s time to actually create the course. It’s sort of like the midterm exam for the instructional designer, because this is the part in the process where the designer gets to test whether he or she conducted adequate analysis up front and/or whether he or she thought of EVERYTHING in the design plan.

Even the best laid instructional plans with the most savvy and talented development teams behind them are going to reveal room for improvement. It may be as simple as adding more graphics or changing a font. The testing may reveal that some of the learner activities which the designer envisioned as absolutely captivating may be as boring as watching hair grow, or that they don’t match the evaluation or assessment of content mastery, or that

Even the best laid instructional plans with the most savvy and talented development teams behind them are going to reveal room for improvement. It may be as simple as adding more graphics or changing a font. The testing may reveal that some of the learner activities which the designer envisioned as absolutely captivating may be as boring as watching hair grow, or that they don’t match the evaluation or assessment of content mastery, or that